CHAPTER 17 - See No Evil

My mum and my aunt took my sister and my cousins to see a show. They took me as well.

It was fantastic. We'd never seen anything like it before. Well, I hadn't, I knew my sister hadn't, and I don't think my cousins had because they said so.

There was this man who told us funny stories and made fun of us. Then there was a lady who rode around the stage on a bike that only had one wheel. One of my cousins said it wasn't a bike because it didn't have two wheels. And there was a man who blew fire out of his mouth, and another man who put a lady inside of a box and sawed the box in half. My sister got upset until the lady was put back together again. He also pulled a rabbit out of a hat, the same rabbit that was in a box, but it wasn't in the box anymore because it was in the hat.

. . .

I went to tell the rabbit that this magic man could pull rabbits out of hats. The rabbit was not amused.

"He was a magician," sneered the rabbit.

"He was good. He made things disappear and come back again," I said enthusiastically.

"Things don't disappear and re-appear," explained the rabbit. "It was only an illusion. To believe otherwise is simply a delusion."

"What? What's an illusion? What's a delusion?" I asked.

"What you saw was merely a trick - a sleight of hand - a deception. If you really believe that what you saw actually happened, then you are under a delusion - a false belief. Regardless, it takes a lot of skill to be a magician, but there is a lesson to be learned from all of this."

"I came to tell you about what a great time I had..."

"Watching rabbits having their ears pulled off?" interrupted the rabbit.

"...and all you can do is give me some stupid lesson - what lesson?"

"How the eyes and brain work together, or not work together, which is more often the case," answered the rabbit.

"The eyes see stuff and the brain thinks stuff and that's all there is to it... Isn't it?"

"Not entirely! The eyes do the seeing and then send the information to the brain, and it is the brain that turns this information into mental images. These images can be recalled later from your memory, assuming, of course, they were stored in your memory in the first place."

"I remember stuff," I added.

The rabbit ignored my remark and continued. "Unfortunately, the brain cannot cope with the flood of information continuously coming in from the eyes, and so it learns to be selective about what it thinks is important. Consequently, it remembers only what it thinks is important and rejects the rest, and there lies the weakness - sometimes it doesn't know what to remember. For example, you may see something happen at a given moment in time, and a few moments later, your brain receives new images that apparently contradict the previous ones, and so your brain desperately tries to reconstruct what it thought happened between the two events, but unless the brain noted everything that happened within this period, it won't be very successful."

"Why?"

"Because, your brain cannot recall what it never remembered."

I frowned in an attempt to understand.

"But as far as you are concerned, you think you saw it all happen, and hey-presto, an illusion just occurred."

"What?"

"The brain doesn't see anything," said the rabbit. "It just interprets the messages coming in from the eyes, and for the most part, it is good at what it does. However, it gets to the point where it only remembers what it deems necessary. When your brain detects something which it cannot explain, it often uses its experience to reconstruct what happened, and this manufactured image can be so vivid that you are convinced that what you think you saw, was actually what you saw."

"Are you saying that my eyes and brain are not seeing the same thing?" I asked.

"In a way, yes! Let's just say that the brain gets a little bit creative sometimes and doesn't necessarily tell you when it's giving you factual information or images that it created. If your brain does manage to reconstruct the images, they become real. If it can't, then you call it magic!"

"That's stupid!"

"All right! How about an example? Don't go away. I'll be right back."

The rabbit left for a moment and then came back, as promised.

"Now tell me about the rabbit in the box trick," requested the rabbit.

"Where did you go?" I asked.

"Never mind. Tell me about the rabbit trick."

"Well, this man gets the box and shows everybody that it is empty. He then got this rabbit - it was a white rabbit. Not a brown dirty coloured one like you. Anyway, he put this white rabbit inside the box and closed the lid. He then takes his hat off and puts it on the table. It was one of those big tall hats."

"A top hat."

"I suppose. He then gets his wand and says some magic words, and pulls the rabbit out of his hat. He then opened the box, and the box was empty."

"Now that was an illusion because your brain thought that it saw everything, but in its wildest imagination, it could not explain how the rabbit apparently went from the box to the hat."

"Yeah! That's right - it was magic!"

"Magic is the gap between what you see or hear, and what you understand."

"That's right - it was magic," I repeated.

"If you say so," said the rabbit.

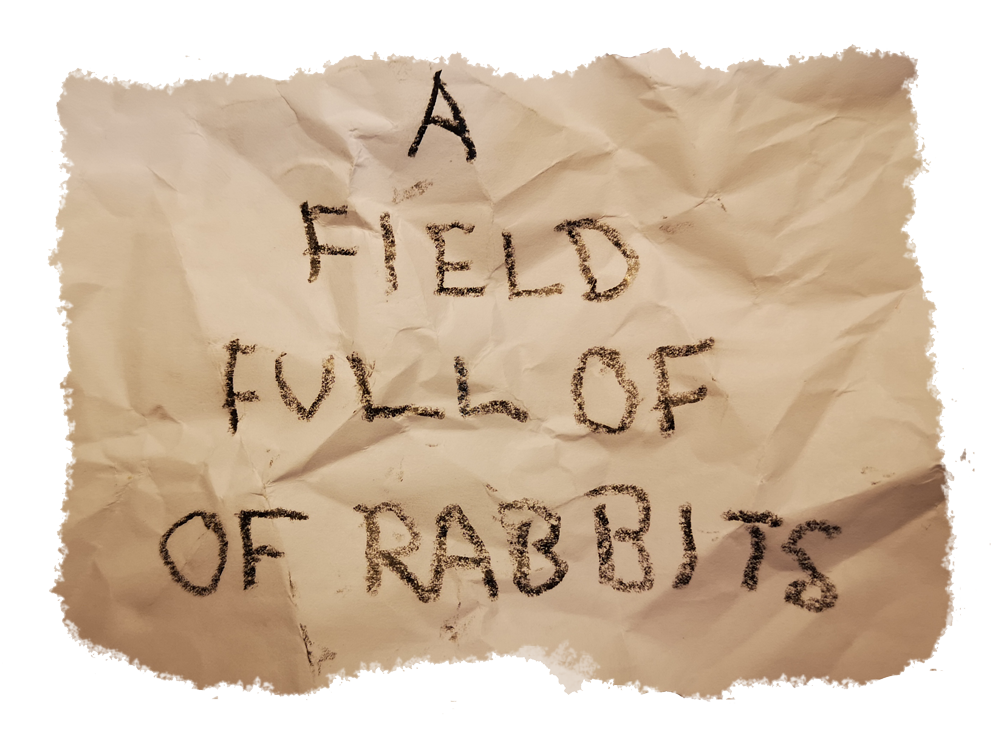

Just then a piece of paper fell into the hole. I picked it up. It had something written on it.

"How did this get here?" I asked.

"Magic!" replied the rabbit sarcastically.

"Should I read what it says? I can read, you know!" I said getting prepared to read what was written on the paper.

"It doesn't say anything," said the rabbit, "but please, read what is written on the paper."

Ignoring the rabbit's wittering I said, "It says, a fi ... eld ... um ..."

"Field," prompter the rabbit.

"I know. I was getting to it - a field ... fool ... full ... a field full of ... rab ... bits - rabbits! A field full of rab ... bits. A field full of rabbits," I said pleased with myself.

"Read it again."

"A field full of rabbits."

"Read it carefully."

"I did."

"Then read it more carefully."

"How can I read it more carefully than I already carefully read it?"

"Put a finger under each word as you read it. Now read it again," suggested the rabbit.

I read it again. "Uh-oh!"

"Your eyes saw it, but your brain decided to form its own image."

"Wow! That's weird. Wait till my sister sees this. She can't read."

"Then there is not much point in showing it to her, is there?"

"Oh yes, that's right," I said. "So, what does this mean? That I can't read no more?"

"No. We sometimes tend to see only the things that we want to see. When your brain starts filling the gaps between what it actually sees, all it can do is fill those gaps with images based upon your familiarity and attitude towards whatever you are looking at."

"What familiarity? What attitude?"

"You know that the sentence, 'a field full of of rabbits', doesn't make sense, and therefore, your familiarity with what does make sense overrode what your eyes saw and what your brain deduced from what your eyes saw."

"?" I just opened my mouth, but no question came out.

"Do you understand?" asked the rabbit.

"No," I uttered.

"Then try this. Hold your left arm straight out in front of you."

I held my arm out.

"Your left arm."

I switched arms.

"Now hold up your index finger - straight up."

"Which one is my index finger?"

"The one you point with."

"I point with my right finger."

"Just hold up your left index finger," said the rabbit getting agitated.

I held it up.

"Good! Now hold out your right arm off to your right and a little lower and hold up your right index finger.

I did that.

"Now, close your left eye."

I put my hand over my eye.

"Close your eye. Don't cover it."

I put my arm out again with my finger pointing up and squinted until I closed my eye. It wasn't easy, but I did it.

"Now stare at your left finger and slowly move your right finger closer to your left finger."

I slowly moved it closer. "What's going to happen?"

"Focus on your left finger but notice what happens to your right finger."

"Oh. It went away."

"Yep!" said the rabbit proudly.

"That's weird. Why did that happen?"

"There's a blind spot in each eye," explained the rabbit.

"What blind spot? I ain't blind."

"It's a good job that you are able to see better than you speak, otherwise you would never find your way anywhere."

"I aren't blind," I said attempting a correction.

"Oh dear!" sighed the rabbit, but continued. "In each eye there is a blind spot where the optical nerve is joined to the back of the eye, but that's not important. What's important is that you are unaware of it. You don't see two black spots do you?"

"No. Why's that?"

"It's because the brain just doesn't think that it is important. What one eye doesn't see, the other does and vice versa, but the reality is, with one eye you just cannot see anything in your blind spot. And when you close one eye, you are still not aware that you cannot see in your blind spot...

"Why's that?"

"It's because your brain does not see what your eyes detect, and it doesn't remember what it doesn't know."

"I don't believe you!"

"If you don't believe that, then you won't believe this."

"Believe what?"

"Until your brain first understands what is coming in from the eyes it thinks everything is upside down."

"No it ain't!"

"You know that and I know that, but the images entering your eye are inverted by the lens in your eye, so your eye gets upside-down pictures which it sends to the brain. After a while your brain realises that they are upside down and turns them the right way up."

I sat and looked at the rabbit and tried to imagine him upside down sitting on the ceiling of the rabbit hole. "You're right. I don't believe you. Next, you'll be tellin' me that sound is upside down."

"No. The eardrums don't invert sound..."

"I was only bein' funny."

"You're right. I do tend to get serious when I get excited."

"You're excited?"

"Yes. This is exciting stuff. Some of the more skilled rabbits try to run in a fox's blind spot, but alas, it's not that effective because the fox uses binocular vision. By the time we are in the foxes monocular or peripheral vision, we're also no longer in their blind spot."

"Oh." Now I was really lost. "You mentioned attitude," I interjected, trying to find something else to talk about."

"Oh yes - attitude!" said the rabbit with a smile.

"Oh, dear!" I sighed, thinking that I had started something I was going to regret.

"Attitude! Not only does your brain be selective about what images it thinks it should remember, but it also remembers certain images - images based upon its attitude."

"I'm sorry I asked. You mean it ... um ..."

"Yes," agreed the rabbit, agreeing with something that he obviously thought I was about to say.

"The images it stores in your memory are only loosely based upon the images that your eyes actually saw."

"You mean ... What do you mean?"

"For example, if someone had an attitude that everything was hard, they would see life as a struggle. They would look for and remember images of potential problems. Consequently, when they replayed those images in their mind, they would see everything as a problem."

"But what if something was a problem. You told me that you can't change facts."

"That's right, you can't change facts, but this isn't about facts. These people would see reasons why something would fail instead of why it could work."

"They would?"

"Yes. See this tunnel?"I looked down the tunnel nearest to me."Not that one, this one."I looked over at the tunnel nearest to the rabbit."Yes. What about it?""Well, we asked two rabbits to dig it as we needed it to join two networks together. One rabbit said that soil was to loose and the roof would fall in. He said that there were too many roots in the way and that it was too far, and he refused to help. The other rabbit didn't agree, so he started digging.""And it was okay," I stated, looking down the obviously fine tunnel."Oh no! The soil was too loose, and the roof did fall in. There were a lot of roots, and it was a lot longer than anyone of us had anticipated, but you never saw such a proud rabbit when he got through to the other network. It just has an extra exit hole where the roof fell in.""What happened to the other rabbit - the one that said it couldn't be done?"

"Oh him? When the roof fell in, he spent the rest of the day saying, 'I told you so! I told you so!' But the point is, both rabbits' eyes saw the same thing, but their brains saw something entirely different. One saw a problem, and the other saw a challenge."

I got up to leave - the piece of paper still in my hand.

"Where did it come from?" I asked, holding out the paper.

"We magicians never tell our secrets," said the rabbit smiling.

. . .

When I got home, I found an empty box. Actually, it had some old photographs in it, but I emptied them on the floor. I just wanted the box. Next, I needed one of my sister's dolls which I put inside the box. Then I went to my dad's shed - got a saw and sawed the box and the doll, in half. This was the moment my sister walked in.

They tell me that it was a brass ornament that hit me, but all I can remember is that my brain saw a lot of stars.